California, Nevada, Arizona, Utah, Colorado…

We crossed the Nebraska border on June 11th near Julesburg at the end of another long day of walking. We were doing twenty-milers now to make up for the time we’d lost back in Barstow, and summer was coming on strong. The main march left early in the morning to catch the coolest part of the day. With three rest stops and a lunch stop, we usually arrived in camp by around four o’clock in the afternoon.

The next morning I woke up late because I didn’t hear the wake-up call, and that, as Frost put it, made all the difference. I rushed to pack up, left my daypack with Peter and Johanna in their van, and headed out with only my Walkman, camera, rain jacket and water bottle, all hanging from my belt. I was far behind the main march with no one in sight ahead of me and no one behind.

Walking across the flatlands was proving to be difficult and uncomfortable in ways I had not anticipated. I had thought that the greatest physical challenge would be the passage over the Rocky Mountains, but the flat, featureless terrain of Nebraska was quickly becoming my nemesis. Before the peace march, my whole worldview had been crafted from shadows and light, dimension and shape. My sense of reality, beauty, action and security were all dependent on my mind’s busy perception of objects—a high rise apartment building, a dense forest of deciduous trees, a long road overlooking the river, a crowded traffic circle, the distant hills of a golf course. Except when I was vacationing at the beach or driving through the countryside, there had hardly been a long view of more than a few hundred yards in my suburban east coast life. Now I was in Nebraska. In the past, I had heard people complain about the monotony of driving across the Great Plains. Some years earlier, I had driven across Kansas, Nebraska’s neighbor to the south: seventy miles per hour in an air-conditioned station wagon, munching a bag of pretzels, singing along to popular tunes on the tape deck. On the morning in question, I had at least two hours of solitary walking ahead of me before the lunch stop. Unlike Robert Frost’s dilemma, there was just one road, but I knew there was a choice to be made—inside me. For the first time, I started to enjoy the quiet solitude of walking across the plains, just me and the road and the vast expanse of Nebraska. By the time I arrived in the tiny town of Brule, my mind had traveled an entire morning without struggling against Nebraska’s open space. I had ceased yearning, at least for a couple of hours, for what was not there—a church steeple, a mountainside, a stand of trees, a city skyline—and had instead begun to accept what was around me—miles and miles of empty space. It was only one morning’s peace of mind, but at least I knew it could be done.

The town of Brule, about six blocks wide and six blocks long, had a banner up on State Street that read, "1886 - Brule Centennial - 1986." The tiny town was a hundred years old. It was hard to imagine what had changed here over the century. How much smaller could the town have been back then? On every street, American flags hung from holders on the telephone poles. As I walked into town, I encountered a woman, obviously a local resident.

“Hello,” I offered.

“Hello,” I offered.

"Hello," she replied reluctantly.

“The town looks nice with all the flags hung out for the centennial.”

She knitted her brow and said flatly, “The flags aren't for the centennial. I keep the flags at my house for the Fourth of July celebration, and when we heard you were coming, my husband and my son and I took them out and put them up around town.”

|

| The Tiny Town of Brule Hung American Flags for Us |

From her unsmiling demeanor I guessed that the gesture was one less of welcome and more of challenge to our political views.

“Well, thank you for welcoming us,” I replied anyway.

“Well, thank you for welcoming us,” I replied anyway.

She nodded, though her guard was still up.

“And please thank your husband and son, too,” I added.

There was no, "You're welcome," but when I asked, she directed me to the town park where the marchers were having lunch. On the surface, I brushed her off as just a grouchy old woman, but a little deeper inside, my brief encounter with the flag woman in Brule stayed with me. Maybe if I had introduced myself and told her I was a teacher, she and I could have talked about our views, however different they may have been. As it was, we left each other with untested, probably inaccurate perceptions. It bothered me that I had not done more to engage her. I was walking on the Great Peace March, but I hadn’t yet learned what it meant to be a peace marcher.

I spent the afternoon walking with the main march, talking and listening to music. Evan and I listened to Penguin Café Orchestra and Andreas Vollenweider on my Walkman. We were both interested in Vollenweider's new definition of harp music. He was playing the instrument in a completely new way, moving beyond the folk and classical traditions and yet incorporating both into a new sound. It must have been a similar phenomenon when people first heard Scott Joplin play ragtime on the piano, his left hand deftly playing both the bass line and the rhythm chords and the right hand surprising the listener with a syncopated melody. These were musicians who, above all, had actually learned to play their instruments. Penguin Cafe Orchestra, on the other hand, was light entertainment. These were folks who played decently well as individuals but together proved a sum greater than its parts. They used non-musical instruments like telephone and rubber band in their compositions - an instant hit with us. Generally speaking, I leaned toward folk and Evan steered toward hard-driving punk, but we were open to what the other thought was good and never tired talking about music.

In camp, I escaped to the Bookmobile to get out of the sun. It wasn’t any cooler on the bus, but the books distracted me from the heat. I finally read Dr. Seuss’s Butter Battle Book. People had been recommending it to me for years, so I had high expectations. The book introduced the topic of an arms race and ended with two groups of little Dr. Seuss creatures on the brink of blowing one another “to smithereens.” It was not a funny story; it contained no comic relief, and it offered a bleak ending with no hope of resolution. As far as I could see, the Butter Battle Book was a Dr. Seuss un-kids book, and it worried me that adults were reading it to little children.

I browsed some more and found a book on walking meditation. The idea had never occurred to me. I thought meditation required a person to sit still in a quiet place. What liberation. Meditation and movement could go together? Well, then, why not meditate while washing dishes or mowing the lawn or picking through green beans at the grocery store? Why not while putting up one’s tent or standing in line at the porta-potties? It gave me great comfort to realize that even a person in the worst of situations—in bed during an illness or even captive in a prison camp—could find solace in meditation. As I stood there on the Bookmobile, it dawned on me that meditation could happen anywhere, and I knew it would became a part of my life.

Over the next few days, I started meditating on the march. I was still walking in three-quarter, waltz time. I chanted a simple “Om” as I walked along. At first it was difficult, but after a while I could chant and walk and breathe. I started to experience the vibration as well as the physicality of my body. I felt the possibility of adjusting, like an astronaut adapting to outer space or a scuba diver acclimating to the sea, to a whole new environmental medium—a silent land with a distant horizon that hung like an empty clothesline across the big Nebraska sky. With an eternity of time and no interruptions—I could see a grain silo literally miles away—walking meditation became my refuge.

Our community was scheduled to elect a new board of directors. We had a candidates’ forum on June 13th with a brief speech from each of about twenty candidates, of whom we would elect seven. Some expressed noble ideals but little practical experience when it came to overseeing the peace march. Some appeared not to comprehend the role of a board of directors and offered detailed plans on how they would manage the day-to-day march. Fortunately, several marchers proposed plans that were balanced, practical and to the point. I listened and hoped we could elect a new group that would get the job done in peace so we could get on with our work and walking.

We followed Route 30 through Ogalalla, Roscoe, Paxton, Sutherland, and Hershey. Each town was an oasis where we could buy a carton of lemonade or iced tea and rest for a few minutes in the shade. Between towns, there wasn’t much to see. Cars passed, and their drivers and passengers reacted in predictable ways. Some smiled and waved; others laughed or sneered and gave us the finger. Some looked straight ahead as if they hadn’t noticed hundreds of peace-signing pilgrims trudging toward them along the highway.

|

| Nap in Scant Shade |

Trains came by frequently on tracks running parallel to our route, a mile or two off to the south and closer as we came through towns. Sometimes the engineer blew the train whistle to say hello. I imagined the engineers contacting one another to keep track of the Great Peace March, just as the truckers must have done. They were probably amused to see us walking their route. Most trains were comprised of several engines pulling a long load of coal or brand new cars. I watched to see if the train had a caboose, then if it did, I called out like Ed McMahon introducing Johnny Carson to anyone walking with me, or to the universal sky, “Theeere’s the caboose!” and kept on walking. Other times, I sang “Little Red Caboose,” a nursery song I’d learned as a child, but only if the caboose was red, which, alas, was rare.

On Father’s Day, June 15th, wake-up came at about 5:30 in the morning. We had to be on the road in time for a rally in the city park in North Platte. I was late, so I walked well behind the main march with my prayer beads to keep my mind occupied. I spotted Evan up ahead at a good distance. He was walking, headphones on, at a brisk, steady pace, stretching his arms in the air above his head with every few steps. With his six-foot-plus frame, Evan looked as though he might breast stroke right up into the sky. It took a while, but when I finally caught up, he greeted me, as he often did, in honor of the song we loved to sing together. “Well, hello, Lucille!” he said cheerily.

I had invented a name for him, too. “Hello, Leonard Foxy Guy!” I returned. We both laughed and walked the rest of the way into North Platte. Along the way, Evan very kindly gave me one of the nicest compliments I’d ever had. “Lucille,” he said, “you never make me wonder.”

At the rally, a group of veterans took the outdoor stage and made brief speeches about the peace march and what it meant to them. Dev, a rough-hewn man with a hefty frame and a serious demeanor, was among them. He stepped up to the microphone wearing his army jacket, as always. He spoke clearly and deliberately. He had worn the jacket every day since his return from Vietnam more than a decade ago. This was Father’s Day, he said, and on this day he was going to take his army jacket off, and he was never going to wear it again. We all clapped and cheered, and some shouted out, “We’re with you, Dev!”

Others added, “Dev, we love you!”

Dev continued. He wanted us to tell us what he was planning to do with his old army jacket. I thought maybe he was going to burn it, but Dev had a better idea. He said that after the march, he would put the jacket in his attic, and he imagined that someday years from now, his son would find it and bring it to him and ask, “Hey Dad, what’s this?” and Dev said he would answer, “Well, son, a long, long time ago, before you were born, we had this thing called war…” and we cheered and applauded again at the idea that war could some day become extinct; and some cried because Dev had expressed so perfectly what it meant to be a soldier and a peacemaker and a father and a man.

The days were blazingly hot and sunny. Only an occasional breeze saved us from spontaneously combusting. I mentioned the unbearable heat to a visitor in camp. “What do you think is the hottest time of day?” he asked.

I could tell from the squint in his eye that I wasn’t going to get this right, but thinking back to my teenage tanning days, I replied, “Well, I guess it must be around one or two in the afternoon.”

“That’s where you’re wrong,” he said. “It’s hottest at four o’clock in the afternoon.”

I was surprised, but he was a farmer, so I figured he was something of an authority on the weather. He explained that the earth’s surface absorbed heat until between four and five pm, and then slowly started to cool down. “So that explains why I’m so miserable all afternoon!” I replied. “I keep trying to find relief in the hottest part of the day.”

The farmer nodded knowingly and said, “You’d be wise to take a rest before dinner.”

I did my best to follow his advice. It wasn’t hard to surrender to a nap in the four o’clock heat after a twenty-miler in the sun, but I hated waking up an hour later in a puddle of perspiration. My tent offered light shade but denied the afternoon breeze. And my sleeping bag provided a comfortable layer against the hard ground but the polyester fabric stuck to my sweaty skin. On those Nebraska afternoons I woke up cranky, walked to the wash-up trailer, filled my water bottle with cool water, leaned forward, poured it over my head and came up shaking like a dog after a bath.

|

| Adaptation |

We yearned for shade, but it was hard to come by. One day I arrived at camp at the end of a long walk. The weary were sprawled out at the treeless fairground, napping. One lay in the shade of a bus; several had pitched tents under the grandstand platform; and one napped in the sun with his head inside an empty gear crate on which he had placed his hat to make a kind of shade box. Earlier in the day, Libby and I had lingered after lunch on a precious island of shade just big enough for two under a newly planted sapling. In Nebraska, I could have made my fortune selling shade.

|

| Invention |

New marchers joined us from time to time, some as permanent additions; others for a few days as we passed through their hometowns. Evan’s friend, Beth, joined us for a couple of weeks. She was totally excited to be on the march and gradually overcame the culture shock that came with plunging into our tight-knit, loosely organized mobile community. Beth was bright and well read. She was on the quiet side, but she must have had a million questions and didn’t want to seem like a bother, so she mostly observed and listened. As far as I was concerned, any friend of Evan’s was a welcome addition to our group.

Evan, Beth and I went out to find ice cream one afternoon and ended up in a Pizza Hut drinking a pitcher of beer with a marcher named Tom from New Jersey. Tom was one of the most animated people I’d ever met. He had sun-bleached hair, a start-up ZZ-Top beard and shorts tied up with a piece of rope like Jethro from the Beverly Hillbillies. The way he continuously shifted his weight from one foot to the other, I was convinced he could wear out a pair of shoes just standing still. He just as energetically jumped into every conversation. His enthusiasm and humor were infectious, and he quickly became our friend.

|

| Tom and Evan Greeting a Local Supporter |

I felt as though I had some extra time on my hands, so I started thinking about other ways I could contribute to the march. Under Carrie’s leadership, the Great Peace March school was finally settling into place. The younger children had already adjusted to their elementary school-on-wheels, and Carrie had recently added another school bus as a home base for the middle school kids to meet to hang out or do their schoolwork. Carrie was moving forward with the final phase of her plan—bringing the high school kids into the program. Free of the constraints that a normal school and home life would have imposed, the peace march teenagers, like the adults, pushed the boundaries of their existence. They appeared to experiment with every avenue available to them, though our no drinking/no drugs policy restricted everyone, including the teens, at least within camp. Along with colorful, choppy, spiky, shaven hairstyles, fanciful wardrobes and multiple piercings and tattoos, the young people eventually acquired adult responsibilities. They didn’t seem to pine for the familiar structure they’d left behind, and many of them became articulate, outspoken advocates for nuclear disarmament. As time went on, I thought about re-joining the peace march school but never acted on the idea. It seemed to be rolling along just fine without me. I had mixed feelings, of course. I was impressed that Carrie was able to give the children what they needed and glad to see them happily engaged in their program, but I felt ashamed that I had been unable to provide adequate leadership for them.

Instead, I made my way back over to Peace Academy. In addition to outfitting the Peace Academy bus as a resource center for nuclear issues, Ned and Nora centralized the “Community Outreach” program, through which we sent marchers to speak at schools, churches, town halls, rallies and private homes. I had been speaking about the Great Peace March since the PRO-Peace days back in Los Angeles. I liked speaking with people because it kept nuclear disarmament central in my mind and allowed me to articulate my views. It also forced me to consider opposing views. When I asked to be put on the speakers’ list, Ned said they hadn’t had many requests in the sparsely populated Great Plains, but they expected to need people as we reached Chicago and beyond. They would let me know. In the meantime, I decided to learn as much as I could about the nuclear issue. On our rest day in North Platte, I read three more articles in Dialogue: one on the development of the nuclear bomb, one on the history of the arms race, and one on the ideological differences between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

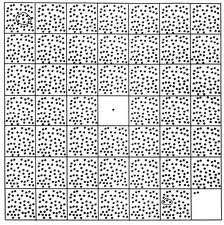

On Peace Academy, I learned how to demonstrate the size of the world’s nuclear arsenal. I was convinced that my ability to communicate this enormous concept was fundamental to gaining support for nuclear disarmament. The key was to contrast the firepower used in all of World War II, a concept with which most people were familiar, with the enormous firepower in the world’s current nuclear arsenal, about which most people had no idea. Peace Academy gave me access to three effective models for teaching this concept. The first was a simple illustration on a piece of graph paper. In the middle of the page, the central square contained a single dot about the size of a period. This dot represented all the firepower of WWII, including both the European and Pacific theaters of war and the two atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The rest of the squares surrounding the central square were filled with thousands of dots—2,667 to be precise—representing the current firepower of the world’s nuclear arsenal. I was shocked when I saw this illustration, as were most people with whom I shared it. No reasonable person, even one who believed in maintaining the greatest military power in history, could think we needed that many nukes.

|

| The Nuclear Arsenal Dot Chart |

An equally effective exercise involved pouring BB’s into a metal coffee can, first just one BB to represent the firepower of World War II. It bounced off the bottom of the can a few times and settled into place. Then came the two thousand six hundred sixty-seven BB’s to represent the current nuclear arsenal. It took a long time to pour all those BB’s into the coffee can, and they were obnoxiously loud. When I first heard them, it sounded as though they were being poured into a coffee can inside my head. I kept waiting for the noise to stop, but in went on for twenty or thirty seconds. The BB demonstration was powerful. People who had had no idea of the extent of our nuclear arsenal were moved to think seriously about disarmament.

The last teaching aid took a humorous approach. The policy of Mutual Assured Destruction, commonly called “MAD,” referred to the fact that both the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. hoped to survive an initial nuclear attack so that they could retaliate with the full strength of their nuclear arsenal. To send a single nuclear warhead against the enemy, on purpose or by accident, was to release the full force of all nukes on earth. Within minutes—twelve to be precise—all nuclear missiles would be deployed and 50,000 nuclear bombs would explode across the planet, each resulting in the scenario described by Jack Geiger in his testimony to Congress. “MAD” was an apt acronym for the policy. In an interview, physicist Carl Sagan had likened Mutual Assured Destruction to two men standing in a room up to their waists in gasoline, each holding up a box of matches, each threatening to light his match first. This image brought a highly abstract concept into the grasp of most people and allowed them a chuckle at our otherwise seriously disturbing state of affairs. I set out to incorporate the firepower graph, the BB demonstration, Sagan's “MAD” image and as much information as I could master, into an effective presentation.

When we arrived in North Platte, a good-sized railroad town about a quarter of the way across the state, nobody could have been more excited than I was to find the public outdoor swimming pool. For a few dollars I had a shower to rinse off the road, a swim to recalibrate my equilibrium, and then another shower to rinse off the chlorine. All that water felt marvelous. Afterward, dressed and refreshed, I sat for a few minutes of solitary bliss updating my journal under the shade trees as I waited for the shuttle back to camp.

In a North Platte health food store, I found a product that made the misery of drinking warm water on a hot day a little more tolerable: dehydrated tea cubes. They worked like bullion cubes but they contained dried herbal tea and sugar. They came ten in a box, and I bought one box each of chamomile, mint, and fruit flavor. I crumbled one into my water bottle at the beginning of the day, added cool water and gave it a shake. Over the course of the morning, as the water heated up, as it inevitably did, I could at least look forward to each swig tasting like warm, sweet herb tea rather than plain hot water. This small improvement encouraged me to stay hydrated.

|

| Portrait: Peace Marcher |

Journal Entry—June 21, 1986

Summer Solstice… Today is the longest day of the year. Cornfields grow taller overnight. Supporters greet us along the street in the tiny town of Odessa, Nebraska. Her sister city in Russia was the scene of the uprising on the battleship Potemkin before the October Revolution.

Sudama, the man in charge of the peace march kitchen, comes over to our tents to talk with Evan and me in the morning. He tells us all about a Hare Krishna program that saves cattle from slaughter. I had learned on the march that the Hare Krishnas, whom I had previously encountered only at major airports dancing and asking for money, are dedicated to preserving life on earth and feeding the hungry. The animal adoption program allows the Hare Krishnas to buy animals at cattle auctions and pay for their upkeep on an animal-friendly farm. Sudama says it cost $3,000 to save a cow from slaughter, and the program includes a photo of the animal, a history and monthly newsletter, and even a parents’ visiting weekend. I have never heard of such an idea. I can appreciate saving the animals from slaughter, but the idea of a parents’ day seems a little out there. Why not return the cows to rolling green pastures where they wouldn’t need to interact with humans at all? I’m not sure why Sudama tells us about this program—he has never spoken with us before—but I am honest about my mixed reaction, and he seems to take it in stride.

Summer Solstice lunch stop in a lush, green park. Marchers are doing lunchtime dances, music and drama to celebrate the solstice. A group is performing scenes from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” though it is not midsummer, just the beginning of summer. Tom and I join those who are walking around a lake: waddling ducks, wild turkeys, horses grazing on a distant hill, and wildflowers. Is there more than this?

Yes, a moonwalk tonight. It’s rare to have a full moon on the night of the Summer Solstice. A hundred marchers want to go, but just as we are about to depart, a late thunderstorm sends us all scurrying under the trucks and ducking into tents. Tom and I listen to “The Point” on my Walkman while the storm passes and don’t hear the march leaving. We hurry to catch up and get stopped by a policewoman who gives us the third degree. She even asks our mothers’ maiden names and places of birth. It turns out she doesn’t even know that the peace march is in town. Five hundred people passed through town an hour ago, and she has no idea. If she doesn’t know, who does? So, we tell her all about it, and she lets us go. Maybe she thought our story was just too fantastic to be an alibi.

At last Tom and I catch up with the rest of the group. Rainclouds obscure the full moonlight all night long. Weird, alternating cold and warm winds buffet us unexpectedly. Intermittent rain. Heat lightning explodes low in the southern sky like distant mortar fire. A long train blows by in the dark. Against a backdrop of flashing lightening, a silhouette of war vehicles, mostly jeeps and Army trucks and tanks, on the back of the train. They rattle my insides. They are going to war. Hunched over in the rain, we move like an anonymous line of refugees toward the east. The whole scene is frightfully possible.

My Walkman saves me from midnight delirium. I groove along. I act out the songs. I sing out loud. I keep everyone around me awake, and, for once, they appreciate it. Stevie Wonder, Bill Withers—my friends. At the third rest stop, marchers collapse in Gore-Tex heaps in a deserted old gas station. Sleepers are strewn like litter on the concrete. I dance in the drive-through garage. It’s a dance marathon—you just have to stay awake. Second wind. I’m up.

Eventually, the sky lightens, and then the sun appears in front of us. My eyes sting, my sweat glands activate. Another sweltering Nebraska morning. We approach our campsite. Can it be? Long tables set up on the roadside entrance and friendly locals serving fresh fruit salad from huge bowls. It’s juicy and delicious and colorful and sweet. I gush my thanks, because the fruit tastes so good, but also because I am utterly exhausted. Up the driveway, it’s a school that has opened its doors to us. An amber-colored, air-conditioned gym. Running hot water. I brush my teeth and collapse in my sleeping bag on the cool, smooth gym floor.

Summer Solstice—the longest day of the year.

I slept all day until four o’clock in the cool, amber gym at the Platte Valley Academy. Images from the previous night returned again and again: rainclouds obscuring the full moonlight, weird, warm winds, the exploding southern sky, war vehicles on the train. Tom and I talked while we shot hoops in the school gym. I liked the sound of a basketball bouncing on a polished wood floor, echoing up into the rafters, and the satisfaction of an angled shot that hit the backboard just right or a long arc that dropped—swish—through the net. Basketball was my favorite sport. Tom was unduly impressed that I could make a shot; to me it was just a way to pass the time. It was too bad that Iris was still away; she would have liked relaxing in the big gym. She sent us a post card of a huge momma sow nursing her little piglets. I hoped she’d get back soon.

|

| The Amber Gym |

After dinner, Evan and I walked down a dirt road between the cornfields as a gorgeous full moon rose behind the grain elevators. Four moons and a thousand miles since White Oak. As usual, we shared every thought that came to mind. I said this would be the perfect place for a UFO to land, right here in the middle of nowhere. I wondered aloud whether there really were UFO’s and, if there were, whether I would really want to see one. Then, just as we turned back to camp, a car came toward us with its bright beams on. We melodramatically shielded our eyes and laughed at this alien encounter, but this time the UFO came in the form of an open Oldsmobile Cutlass convertible packed with three middle-aged men and their three middle-aged female companions. They pulled up alongside us and stopped. They were absolutely smashed and asked us who we were, where we were from, what we did, if we wanted to buy any “smoke,” and if we wanted a couple of their beers. We readily answered their questions and politely declined their proffers. They told us they were high school friends from the tiny town of Shelton. What a bunch of characters. They wanted to know if we were married or tented together, then they refused to believe that we were not married, that we slept in separate tents, and that we were just friends. They threw back their heads and laughed, their arms slung around each other, and said, “Don’t tell us about friends!” And off they sped.