Beautiful chains of mountains surrounded us all the way from Salt Lake through Provo, east through Green River and into the Colorado Rockies. Everywhere I looked there were mesas, mesas, mesas. Tim, Evan and I shared the driving and listened to tunes on the tape deck. I heard “The Catherine Wheel” for the first time, a surprise gift from Sheila, who knew I liked David Byrne’s music. Afternoon eased into evening, and evening into night. We found the peace march encampment in Grand Junction. Rather than try to pitch tents in the dark, we settled down to sleep in Sage. The next morning we awoke to find only vehicles in camp. Everyone was in Marcher-in-the-Home. We stored our gear on the gear trucks and greeted our friends as they slowly trickled back into camp. I was relieved to feel healthy again, and grateful to Tim for his hospitality. We asked him if he would consider rejoining the march now that we were up and running, and I thought he might say yes, but he said he had things to do in Salt Lake, so we exchanged long embraces and bade fond farewells and waved as Tim and Sage headed back to Utah.

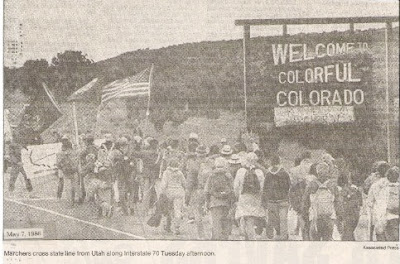

As in any community, marchers left to visit other places, attend family functions, tend to personal business, make spiritual retreats, even march on other marches. Many had taken advantage of the Salt Lake detour to leave the march for any number of reasons, but we all rendezvoused at Grand Junction on the tenth of May to begin our trek over the Rocky Mountains. The only ones missing were the Spirit Walkers, who were, we supposed, somewhere in southern Colorado, making their way northward toward our eastbound group.

We gathered in “city mode” and walked through Grand Junction behind our banners and flags, now including the Colorado state flag. In the early morning light, newly leafing trees dappled the sidewalks, and tiny buds appeared on shrubs, hopeful signs of spring. Coloradans in their bathrobes and sweat suits stood on their porches, steaming mugs of coffee in hand, waving and shouting kind wishes. Little clusters of people applauded as we passed. Some held up signs: “D.C. or Bust” and “Feet, Not Arms,” along with the ever-present peace sign. Parents let their children run out in pajamas and slippers even though it was a chilly morning, because it was only once in a lifetime that they would see five hundred people walking through their neighborhood on their way across America.

|

| Portrait: Peace Marcher |

We continued out of Grand Junction along a manmade, concrete canal that ran for a mile or two, apparently part of a flood control system. We shared a route with the highway, the railroad tracks, and the beautiful Colorado River. At times, mountains loomed steeply to the north, while sunny, rolling farms spread away to the south. At other times, our route took us through the deep shadows of narrow, winding, mountain gorges where the river gushed nearby. On the high plateaus, the land occasionally widened on both sides of the river and we enjoyed long views across farmland framed by a ring of majestic mountains. The air must have been full of negative ions. It smelled fresh and clean, and I felt happy and high. The river rushed and sparkled in the sunlight all day and hushed us to sleep at night. Route 6 took us through Akin, Parachute, Rifle, and New Castle. A group of Spirit Walkers returned from their journey exhausted and bedraggled but all in one piece and proud to have prevailed on the grueling trek. They reported that another group of Spirit Walkers who had split off to hike through Cottonwood Pass a little farther to the east would meet up with us in a few days, near Vail.

On May 15, we arrived in the pretty spa town of Glenwood Springs where we set up camp in a park by the river. At the center of town were an enormous outdoor swimming pool and an impressive resort lodge of red stone. The town was peppered with quaint hotels and casual boutiques. Relaxation seemed to be Glenwood Springs’ stock in trade.

It was a rainy rest day. Many marchers opted to visit the mineral springs for a soak; others headed out on a white water rafting trip. Iris and I were short on funds, so we walked through town window-shopping until lunchtime when we happened upon a Hungarian restaurant. The menu in the window looked promising and not too expensive, so we stopped in. I ordered the borscht, the least expensive dish on the menu, hoping it would come with a slice of bread to round out the meal, and it did. The owner spotted us as peace marchers and came over to our table to introduce himself. He pulled up a chair and sat talking with us, briefly at first about the peace march, and then at length about his experiences as a young person living behind the Iron Curtain. He described, with some emotion, the daily restrictions the Soviet government placed on him and his friends and his family. They couldn't speak freely or travel outside the soviet block countries or gain access to books. A march like ours would have been unheard of. I listened intently. This man had intimate experience with the communist system, our ideological enemy and the primary reason for the nuclear arms race. I was looking for the flaw, the hole in the fabric that would allow a ray of hope that people living behind the Iron Curtain could somehow transform totalitarian control into democracy. One contradiction in what he said puzzled me. I hesitated as I mustered the courage to ask what I hoped was not an insensitive question. “With such severe restrictions on opinions and individuality,” I said, “how do you explain yourself, a free thinker, as a product of communist society?”

His abrupt silence worried me for a moment. Had I inadvertently struck a nerve that would reverberate in an angry response? I pictured him slamming his fist down on the table and throwing us out of his restaurant. After another moment the man replied, “That’s a very good question. I hadn’t thought about that before.”

I breathed a little sigh of relief. He went on in a more reflective tone, explaining that despite totalitarian control, people continued to think freely, even if only internally, waiting for the moment to break free. Iris suggested that maybe there was hope that free-thinking people from both sides of the Iron Curtain could someday meet and find a way to overthrow repressive governments and live free of antagonism and fear.

“Yes,” he conceded, “I suppose it is possible.”

Glenwood Springs Elementary School kindly offered their all-purpose room for musicians to rehearse, and several of us jumped at the opportunity. One of the teachers came in and asked if any of us would be willing to visit her classroom to speak with her kids. A few of us volunteered and found ourselves with the fifth grade class, a well-informed, enthusiastic group of children, and, best of all, a class primed to ask probing questions. Each of us took turns telling stories to help the children imagine life as a peace marcher. We told them all about what the camp looked like and how the kids on the march went to school, how we made our meals and did our laundry and went to the bathroom. They were open-minded and curious and comfortable speaking with adults. When we were near the end of our visit, a hand went up, and one boy asked a question that stopped me in my tracks: “What if we have a war before you get to Washington?”

It wasn't the first time I'd discussed the nuclear arms race with a class of children, but I had to stop for a moment and take a breath. He had innocently put his finger on my greatest fear, my last thought as I lay in my sleeping bag at night waiting for sleep: What if it happens tonight? What if someone sends up the big one before we have a chance to convince our leaders to rein in this madness? This little fellow harbored the same worry. He was only ten years old. I had to answer his question honestly, but I also had to throw him a lifeline.

“You know,” I answered carefully, as if I had been thinking about it for a long time, because I had, “I don’t think that’s going to happen.”

Another marcher, Toby, immediately read the situation and smoothly joined in, “I have it on good authority that we’re going to make it all the way to Washington.” (I knew Toby. If the boy had asked him on whose good authority, he’d have said, “Mine!”)

“And when we get there,” I added assuredly, “we’re going to let our leaders know we want to stop building these bombs.”

The little boy seemed relieved that the peace marchers were going to take care of business, and I was glad to leave him with that impression. I didn’t mind at all knowing that he might sleep better now that Toby and I had shouldered the task of keeping him safe. Silently, I sent out a big prayer that we were right. As we finished speaking with the kids and said goodbye, I thought that someday I'd like to return to Glenwood Springs Elementary School to teach. Someone—their parents and teachers, no doubt—had given these kids permission to think for themselves and the tools to do it well. If they were anything like their written reflections, the children’s dinner conversations at home must have been lively that night…

“If I were in the piece march I would want to be in a blue tent. with Brooke, and Caroline. The part I would not like is when we had to walk. I would not like to go over the Rocky Mountains. If we had to my feet would be very soar. I would go to the BOOKMOBILE every day and get a book. The reason I would be able to read so fast because I read while I am walking. I would wear out my shoes.” – Alicia

“If I went on the peace march I could not stand 20 miles a day 27 miles I hate to think about and even 8 miles is pretty bad. Being in the Rocky Mountains would be fun I would bring my skis and go skiing. I would like to go to Los Angeles and get Raiders and Rams autographs. When I went through other states and cities I would get football players autographs who were on that state or cities team. I would like my tent to be black I would like to share a tent with Richard. When I went through the desert I would bring a water bottle with refill and a black boom box!” — Kenny

“If I was on the Peice March I would like to have a blue tent that was the smallest size with red stripes all over it. Because I like serching around small places. I would go to the piece school every morning. I think she said it was only three hours long and that would be a change and it would be a fun change. I wouldn’t forget that we were walking all this long way to protest nuclear weapons. It would be fun to get your mail everyday.” —Samuel

“If I went on the peace march… I would go because I want other people to realize that the government is spending too much money on nuclear weapons and should be spending more on public school fixing potholes and feading, clothing and housing the poor. I would take on the peace march only enough clothes and nightgowns to last a month because I would wash the clothes. I would also take 5 blankets, 10 boots, 1 flashlight, and my teddybear. I would want to live in an orange tent with my family. I would like to see all the different places because I like to travel.” —Ellen

The following day, we walked from Glenwood Springs to the town of Eagle. The road rose gradually in zigzagging switchbacks through the mountains, but strangely enough, the climb into the Rockies was neither noticeably steep nor particularly difficult. Perhaps it was the thin air and the glorious scenery pumping adrenalin into my whole system that kept my mind off the physical challenge, but more likely it was the simple, amazing fact that I was doing something few people in this century dreamed of doing: I was walking over the Rocky Mountains.

We arrived at our encampment in Eagle, a broad, grassy field surrounding a big, white barn. The Colorado River twinkled nearby, and the pastel blue, yellow, green, orange, and pink of our tents stood out against the bright meadow grasses and the dark mountain pines. I had heard, though I never confirmed, that North Face had recently bought the “Esprit” fashion company, and this was how the “Esprit” pastel colors had found their way into our tents. In any case, it was a lucky break for us that the tents were completed and shipped before PRO-Peace failed because they turned out to be a great calling card as we set up camp in towns all along our route. Local residents who expected to drive past an encampment of drab tans and olive greens instead found themselves enticed into a guided tour amid cheerfully colored nylon domes. More than once I heard visitors describe camp as "a field of giant gumdrops." The town hall tents looked a little like circus tents and lent a festive air. Every peace march venue was unique, but in Eagle, our camp looked particularly vibrant and lovely.

|

| Eagle, Colorado |

The problem of the peace march school continued to trouble me. Every morning I thought about whether I should stay in camp to teach the kids rather than heading out to walk for the day. Some days the children had adults around to provide some structure; other times they seemed to wander aimlessly through the day. The home schooling idea had fallen by the wayside, and there was nothing holding the “school” together but a string of quickly devised field trips as the march moved from one campsite to the next. I thought the kids should be walking for part of the day, but most walks were too long for them, and I was uncomfortable just dropping them off somewhere along the road after we had visited a place of interest so that they could walk the rest of the day. I was slowly coming to realize that for me, teaching required an ordered system, or even a disordered system, but a system of some kind, whereas the Great Peace March school required the creation of order out of chaos every single day. I lacked the confidence, the skill, the energy and the temperament to accomplish that task. Mostly, I didn’t have the resolve. I couldn’t tell whether the kids were learning anything at all even on my outings with them, and I was starting to perceive the glass as half empty.

The road running through Glenwood Canyon was narrow and steep. We were really in the mountains now. Peaks rose sharply on either side of the pass. You had to look straight up just to see the sky. The road was under heavy construction when we arrived, so we all had to ride buses or load into personal vehicles for a few miles. I boarded one of the buses. We crept along and at one point passed the small entourage of Spirit Walkers who had received permission to walk through the canyon despite the construction. We lowered the school bus windows and shouted out to them:

“Woo-hoo! Spirit Walkers!”

“Lookin’ good!”

“Thank you, Spirit Walkers!”

They smiled and waved back and gave us the peace sign.

When we reached the main construction site, the signalman shouted to Dan, our driver, that there would be a lengthy delay; our upward bound side would have to wait for fifteen or twenty minutes to allow a single downward lane of traffic through. In he meantime, Dan let us off the bus to have a look down into the canyon. The sheer rock walls amplified the sounds of the construction machinery and the voices of the workers. Air and mist surged upward from the swollen river rushing below—evidence of the spring snowmelt already underway. I laughed into the echoey canyon as I the energy hit my face. At last Dan called out that our turn had come, and we proceeded out of the cold shadow of the canyon.

Now our campsite was located on the wild mountainside. Our vehicles were parked single-file along the narrow shoulder of the mountain road. We pitched our tents wherever we could find a patch of relatively flat ground. Some camped near the road, others down by the river, still others here or there tucked in behind a cluster of boulders or a stand of trees. The aspens were starting to leaf out, and their lively, fluttering sound filled the air whenever the breeze set them trembling. The new pine growth smelled fresh and the sun seemed ever-closer overhead.

I the morning I awoke to the delicious sound of the river rushing past my tent. A cold mountain shade shrouded the camp. I dressed in the clean, new underwear and socks that my sister Deanna sent. What a treat! Actually, Deanna, in her customary considerateness, sent two sets of socks: the first were soft, thin cotton socks to be worn next to the skin, and the second were colorful, warm, woolen socks, perfect for layering against the chilly mountain air. I thanked Deanna aloud as I put them on. Of course, socks and underwear weren’t enough. On cold days in the mountains, I donned nearly everything in my crates: t-shirt, turtleneck, sweat pants, a cotton jumper, my woolen penguin sweater, my down vest and my blue North Face rain jacket. I accessorized with a grey woolen hat, a herringbone wool scarf, pink gloves, sunglasses, and my Nike Airs. I hung my photo ID on a shoelace lanyard around my neck. Nothing matched. I looked like a little girl who had raided the costume box. Like everything else in “Peace City,” Great Peace March haut couture was nothing if not eclectic.

We arrived in Vail. Condominiums lined the road and dotted the steep mountainsides. There was far less snow than I’d expected. The highest peaks hoarded remnants in deeply shaded ravines, but the lower slopes were balding and streaked with mud. The ski season was nearly over. As we approached Vail, we had great news. The head of the Vail condominium owners association had contacted the owners to let them know that the peace march was coming through town, and the condominium owners, amazingly, voted to open their vacation homes to us. The head of the association was on hand when we arrived, welcoming us with wild enthusiasm including a mysterious ritual of breaking open a watermelon with a sledgehammer in honor of our trek. Iris, Sheila, Joel, Evan, Bill and I formed a group and were assigned a room in “The Antlers.” Our condo had few of the plush amenities of some of the other lodges, but long, warm showers, soft, cozy beds and fresh, clean linens were luxury enough for us. The condo owners could easily have offered us an outdoor site in Vail, but they took a chance and in their absence let several hundred road-weary travelers stay in their homes. Many marchers affectionately referred to our two nights in Vail as “Marcher-in-the-Condo.”

Fergus had joined forces with a group of talented musicians to form a peace march band. They lived together during the three months since we had set out from Los Angeles, and music became their central purpose on the march. Fergus and Art played guitars and sang, Toby and Linda sang back-up and lead vocals, Joel and Bruce played congas, and Ty played the flute. In Vail, they arranged to play at a local bar and invited several other musicians to join the bill. It seemed like a night for lively tunes, and I hadn’t written anything upbeat, so Hannah and Georgia and I sang a song called “Long Walk to D.C.,” a blues tune that the Staple Singers made popular during the Civil Rights Movement. It was a rambling song that didn’t really have a chorus to lean on; it was hard to keep from turning the beat around; and it was a challenge to stay on our harmony parts, but we managed to get through it and have a good time. Some of the other performances were much better than ours. Linda, Hanna and Georgia sang a spot-on rendition of “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy.” This struck me as strange as I had had a dream before the march began in which a trio of women was singing exactly that song.

My favorite performance of the night were the two guys did a skit about the greeting we got from the workers in camp who applauded and cheered as the marchers arrived at the end of the day. They called it the "woop-dee-doo." The gist of their skit was that, sure we were marching for global nuclear disarmament, but mostly we did it for the “woop-dee-doo.” Performing for a group who sometimes took ourselves a little too seriously, the two guys struck exactly the right chord to make us all laugh at our high-and-mighty motives. Fergus and the rest of the peace march band rounded out the night and everyone danced, celebrating the generosity of a well-heeled little ski town with a big heart.

My favorite performance of the night were the two guys did a skit about the greeting we got from the workers in camp who applauded and cheered as the marchers arrived at the end of the day. They called it the "woop-dee-doo." The gist of their skit was that, sure we were marching for global nuclear disarmament, but mostly we did it for the “woop-dee-doo.” Performing for a group who sometimes took ourselves a little too seriously, the two guys struck exactly the right chord to make us all laugh at our high-and-mighty motives. Fergus and the rest of the peace march band rounded out the night and everyone danced, celebrating the generosity of a well-heeled little ski town with a big heart.