After a while, everyone started to refer to our traveling entourage as “Peace City.” I didn’t really like the name. In my mind, a city was a place with skyscrapers and elevated trains and bustling streets and trucks carrying produce in from the countryside. The peace march was more akin to a traveling circus with all our tents and trucks and trailers. But the alternatives—Disarmamentville, March Town, NoNukesbury—sounded even more ridiculous, so “Peace City” stuck. I didn’t grouse about the name, but I didn’t use it, either. Still, our group did operate in many ways like a well-organized town. In our volunteer work force, we did our jobs because they needed to be done. Our bosses were necessity and purpose. Our bureaucracy was lean. There were hundreds of essential tasks to be done every day, and there were plenty of able-bodied people around to do them. If a job was left undone, we noticed, and usually we didn’t suffer long before someone stepped up to the task.

|

| Keeping the Porta-Potties Empty |

The peace march presented an opportunity to experiment with a new occupation, and many of us jumped at the chance to re-define ourselves and become someone our real lives would never have allowed us to be. Marchers tried their hand at washing dishes, baking bread, keeping finances, organizing the Bookmobile, repairing vehicles, caring for the peace march babies, drawing maps, writing press releases, procuring food from local suppliers, laying out the campsites, keeping the water truck filled, keeping the porta-potties empty, directing traffic, serving as “Peace Keepers” to secure the camp after dark, and doing the dozens of other jobs that together moved “Peace City” another fifteen or twenty miles down the road each day. Back in Barstow, when we desperately needed drivers to move our big trucks, one person who volunteered was a woman named Tina. I didn’t know her well, but, like everyone else in camp, I knew when Tina was training to drive the trucks because we could hear her grinding the gears mercilessly as she figured them out. On the day that she went to the Department of Motor Vehicles to take the exam, we all waited and hoped for the best. Several hours later, Tina, her California blonde hair blowing in the wind and a big, toothy grin on her face, was treated to a mile-long cheering section as she drove by tooting the horn of her big rig to let us know she had passed the test.

|

| Delivering the Mail |

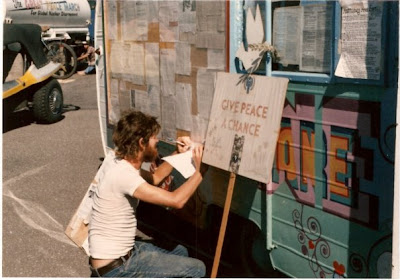

Like any other town in America, our mail was delivered via U.S. Post Office. PRO-Peace had developed a handy schedule so friends and families would know where to send letters and packages to us all the way across the country. Our address was simply “The Great Peace March,” followed by the town name and the zip code. Every day except Sundays, the marchers in charge of the mail service hopped into their yellow dune buggy and retrieved mailbags from the nearest U.S. Post Offices along our route. Our mobile post office was an old blue bus rigged out with alphabetized mail slots. Each afternoon, we lined up and waited our turn to call our name out to the person in the window in the hope of a letter or package. It was always a big thrill to get something in the mail, and we celebrated each other’s good fortune even if we didn’t get anything ourselves. The post office workers occasionally handed out a piece of candy as consolation to anyone who didn’t get mail that day. As far as I could tell, the system worked remarkably well.

Serving Up and Washing Up

After many failed attempts to enforce a strict departure schedule, the community eventually developed a morning routine that allowed most of us to follow a natural rhythm. A group of early birds set out immediately after breakfast with various flags and banners, including the Great Peace March banner. We called them the “main march.” Someone walked through camp after breakfast calling, “The march is leaving in five minutes,” and the main march set out in fairly tight formation behind the flag bearers. The rest of us trickled out onto the road over a period of an hour or so after we finished breakfast, stored our personal belongings, rolled up our tents and filled our water bottles. After everyone who was walking had departed, those who had stayed behind to break down, clean up, and move camp could get to work.

We spent most of our time out on the road talking to one another, waving to people as they drove past, taking in the scenery, listening to music, and occasionally stepping off the road to talk with a local who wanted to know more about our trek or present an argument against disarmament. As for music, mine was Bob Dylan’s Infidels, Pretenders, Andreas Vollenweider, Talking Heads, Jane Siberry, the Penguin Café Orchestra, a soundtrack called “The Gospel at Colonus,” Stevie Wonder, Bonnie Raitt, Bill Withers, and others, or one of the compilation tapes that friends had made for me.

Our procession spread out over several miles, always heading eastward along the shoulder, always facing the oncoming, westbound lane of traffic. Some marchers argued that a tight procession had a more powerful impact on the public; others counter-argued that a long, thin line of marchers gave drivers time to mull over their opinions about the nuclear arms race. I usually left camp about fifteen or twenty minutes after the main march simply because I liked a little elbow room for swinging my arms, and I preferred not to worry about anyone stepping on my heels.

Every day or two, the Info-Com team published The Peace City News. The editor painstakingly typed it and then somehow made copies. The editorial tone was usually harried and prickly, but given our Spartan circumstances, it was amazing that The Peace City News was published at all. It was an accurate, comprehensive source for news about rallies, media events, and opportunities for community outreach. It told us when we could expect Marcher-in-the-Home, where to find community swimming pools and showers, and which local peace groups were supporting us. Marchers posted lost and found notices, the times and locations of in-camp meetings, and a host of other useful information. The Peace City News should have won a Pulitzer: in a mobile community that tended toward impulse and rumor, it kept us informed and connected.

|

| Getting or Posting Information |

The Peace City News was disseminated on the road. When the main march set out, someone procured a copy of the newsletter and read it aloud at the front of the line. As we walked along, the newsletter was passed back from the marchers up ahead. We formed a little cluster and one marcher would hold the shoulder of another for stability and directional support and read the news aloud to everyone within earshot as we all kept on walking. When they were done, they passed it along to the group behind them and so on down the line. Anyone who missed the news on the road could find it posted on the little turquoise Info-Com trailer in camp.

Meanwhile, back in camp, the day’s workers were breaking down the old campsite, loading it into trucks and moving out. An hour or so after we hit the road walking, our vehicles started to appear, passing us on their way to our next campsite somewhere up ahead. As they drove by in trailers, trucks, vans and buses, they gave us the peace sign out the window, and we all returned the gesture.

After the first four or five miles, we spied “porta-potty blue” off in the distance. That could mean only one thing: rest stop. Two marchers, older men who were unable to walk the long distances, drove the porta-potty trucks all the way across the country. We lovingly nicknamed them “Porta-Potty Bob” and “Porta-Potty John.” They kept a supply of fresh drinking water in jerry jugs on the trailers so we could refill our water bottles. On those ill-planned mornings when I found myself chugging down the road desperately scanning the horizon for the unmistakable blue trailer, I was profoundly thankful, but even on normal days, I appreciated “Porta-Potty Bob” and “Porta-Potty John’s” vital service to the community. By the way, the men on the march seemed to have made a gentleman’s agreement not to whiz in nature every time the need arose. To mark their way across America would surely have been taken as an undiplomatic gesture by the local authorities and residents, so it was good that the men used the porta-potties for their business.

|

| Portrait: Peace Marcher |

A little yellow Toyota truck carried food out to the lunch stop. The bumper was covered with bumper stickers—“Love Your Mother,” with a photo of the earth from space, “Visualize World Peace,” and “Arms are for Hugging,” with two little children embracing. The kitchen crew loaded up the back with serving tubs and food and tied a couple of folding tables on top of the truck. I loved seeing the little yellow Toyota drive past, because it meant lunch was coming up soon. By the time we got there, the servers would have set out the folding tables and several plastic tubs filled with sandwiches and fresh vegetables and fruit. They stood behind the tables and called out like carnival barkers what was in the sandwiches or how many carrots or apples or blood oranges we were each allowed. Routinely, I stopped first to use the port-a-potties, then washed my hands and air-dried them as I stood in line for lunch. We ate, usually in small groups, sitting along the side of the road or on nearby rocks or against a tree or wherever Mother Earth offered a place to make a lap. After lunch and a thirty-minute rest to digest and refresh, we hit the road again, talking, waving, flashing the peace sign to drivers passing by, heading for the next bend in the road. Most days we had another rest stop about four or five miles after lunch, and then the last four-mile leg brought us into our next camp—a new “Peace City.”

|

| Lunch Break at the Side of the Road |

The loaders would have unloaded all our gear and placed it into long piles according to the now defunct neighborhood system. As long as the tents and sleeping bags were labeled, the loaders could file them for pick-up. It usually only took a few minutes to find the right tent and sleeping bag and head off to locate one’s friends and make a neighborhood.

|

| Marcher Gear Unloaded and Ready for Pick-Up |

The second day past Las Vegas was a workday for me. I joined a small group of adults who had invited me to bring the children on a field trip. We loaded the kids into two cars and drove to the Valley of Fire, a stunning, red sandstone park and the site of Native American petroglyphs thought to be at least fifteen hundred years old. The children were only mildly interested, although one of the adults was quite knowledgeable on the topic of petroglyphs. With no larger context for their learning, I felt I was just dragging the kids along. Even when we stopped for lunch in the valley, they complained. I didn’t have too many resources to fall back on. I wasn’t the camp counselor type who knew a roster of funny songs or minute mysteries or group games to keep kids occupied. I tried to spark their imaginations by wondering aloud how the Native Americans might have lived in the area, but the kids didn’t go for it. They were hot and bored.

Fortunately, one of the adults discovered that there was a site nearby where we could stop and watch a herd of buffalo. We voted unanimously to take the detour. When we arrived, sure enough, there was the herd grazing about a hundred yards from the parking lot. Buffalo watching was the perfect field trip, providing a story from the past, a “hands-on” experience in the present, and a discussion about the fragile future of these remarkable animals. Besides, the fluffy-headed calves were just adorable. We took our time to read the information placard and watch the herd. On the way back to camp we stopped at a recreation area where the kids had a quick dip in chilly Lake Mead.

The peace march provided opportunities for children to experience learning in a completely unique way, but a lack of continuity kept them from building understanding or reflecting on their experiences. On the two days a week when I was with them, I encouraged the children to read the books they had brought with them and write in their journals, and we sometimes managed to find a way to make that possible, but the kids moved from adult to adult through the week, going on one field trip after another without a coherent program. It seemed to me that unless someone gave up walking to work with them every day, the children would continue to learn through high experiential stimulation and low academic discipline, similar, I imagined, to that of pioneer children heading westward a century earlier. If the peace march children were going to return home to a pioneer lifestyle after the peace march, that would have been okay, but I was worried that their schools might not accept a string of field trips as a bona fide curriculum.

I often thought of the pioneers who crossed the American continent on their westward trek. The Great Peace March managed an average of about fifteen miles a day traveling on blue highways with all our gear transported in trucks. We wore ergonomically designed shoes and had access to modern amenities at least every two or three days. Most of us had given up nail polish, mascara and shavers, but we still had toothbrushes, tampons, sun block and the ubiquitous Sony Walkman (aka Walkwoman). We had generators powering our mobile kitchen, our communications trailer, and our refrigerated food storage truck. Compared with the modern lifestyle, sure, we were roughing it, but we were living the lush life compared with the pioneers in their wooden wagons lurching along unpaved trails. How fast their leather boots must have worn thin, and then what did they do? How painstaking it must have been just to gather wood for a fire to heat water to cook a meal or take a bath. I wondered what they did when someone got sick, how women handled their menstrual periods, and how they managed to find a little privacy for their personal relationships. Like us, they probably established a rhythm to meet their basic needs, and, like us, each person probably contributed to the group’s progress and wellbeing. Like us, they probably didn’t take kindly to slackers.

On the evening of April 15th, we learned that the U.S. had bombed several sites in Libya in retaliation for the recent bombing of a discotheque in West Berlin where two American servicemen were killed and scores of others were injured. Marchers gathered around a small generator-powered TV in the back of a van to watch the news. Faces expressed a range of emotions—sadness, disgust, disappointment and fear—that the U.S. had decided to fight fire with fire instead of continuing to put pressure on the Libyan government through diplomatic means. The peace marchers were dismayed that Ronald Reagan was heaping antagonism onto an already volatile situation. Marchers talked back to the television just as people must have across America when they heard the news: Surely we could handle our power better than that. He’s a warmonger. This administration is a diplomatic nightmare. Congress is nothing but a bunch of criminals.

I didn’t know much about the situation. Other than the Peace City News, I hadn’t read a newspaper in weeks. I disagreed with Reagan’s decision to bomb Libya—though I was sure that Libya’s president, Moamar Qadhafi, was no friend of the United States—and I agreed with my fellow marchers that Reagan’s administration had damaged diplomatic channels around the world in the name of “cowboy politics.” On the other hand, I believed that most of our leaders on Capitol Hill were dedicated to representing the citizens’ views. My tendency to give congress the benefit of the doubt put me in a more conservative camp among the marchers. I put stock in our constitution and the untapped, radical potential of our democracy. As much as we agreed on global nuclear disarmament, The Great Peace March was slowly incubating a community of diverse political perspectives.

|

| The Bookmobile |

After several days of clear weather and uninterrupted walking, we enjoyed a rest day in the tiny casino town of Mesquite, Nevada, an oasis of cleanliness in the desert. The local high school allowed us to use their showers, and we impressed the owners of the local Laundromat with a sudden spike in revenue. In the high school locker room, women of all ages, sizes, shapes and colors peeled off soil-stiffened clothing and stepped into sprays of warm water. We let out spontaneous “aaah’s” followed by delighted laughter. On my second scrubbing, I looked down at my legs and realized that much of what I had thought was dirt was actually skin color. Despite my routine use of sun block, I was Bedouin brown. We shared lotions and sprays and loaned clean clothing to those who hadn’t yet been to the laundry. I was learning the joy of sharing and the grace of receiving in an atmosphere of limited resources. Outside, waiting on the lawn for the bus back to camp, we pretended not to recognize each other and shared satisfied sighs. Cleanliness had become one of life’s simple—and most treasured—pleasures.

The desert environment pitted marcher against sand. A little cloud of dust arose each time I pulled my sleeping bag from its stuff sack or put on my shoes. My pillowcase took on a burlap hue and rough texture. On the days between showers, I reluctantly rubbed sun block cream onto my dusty limbs. One windy evening while finishing a bowl of soup, I examined the granular residue in the bottom of the bowl. A spice I hadn’t detected in the flavor of the soup, perhaps? No, it was half a teaspoon’s worth of sand.

Of greater concern was the sand that found its way into our tent zippers and forced the teeth out of alignment. North Face responded by offering to replace all damaged zippers. Two marchers who were unable to march due to health issues, retrieved their personal van from home and established a service sending the damaged tents back to North Face. Frank and Flo received the damaged tents at their “Tent Repair” van, assigned a “loaner” for the duration, and notified us—via the mail truck—when the repaired tents had been returned. Their practical response to an unexpected need proved to be one of the most valuable and successful support services on the march. Along with Paul Newman’s, North Face earned a place on my list of favorite brands.

|

| Tents vs Sand |

Between Nevada and Utah, we briefly entered the far northwestern corner of Arizona where a Native American community invited us to a big potluck dinner. It was here that the residents of “Peace City” learned an important lesson in community restraint the hard way. Except for the meager Barstow days, we had so far had the good fortune of a bounteous supply of food in camp. At the end of a long day’s walk, even the most ravenous marchers were welcome to eat their fill. At the reservation in Arizona, however, those who arrived earlier at the buffet table did not realize that they should have practiced what my family called “FHB” for “family hold back.” When guests were invited to dinner, a whispered “FHB” meant hold back on seconds until the guests had eaten their fill, and offer to split the last portion in the serving dish. In Arizona, the potluck ran out well before the last marcher had been served, and as one who happened to be toward the end of the line, I felt the embarrassment of our hosts who had made a generous amount of food but were unable to feed us all. We made light of it, and our visit ended on a positive note, but most of us shouldered a lesson in humility and carried it forward down the road.

|

| "We Don't Have Enough Funds Even to Get Us to Denver..." |

One evening, Iris, Joel, Evan and I were sitting around after dinner. “If you could have any vision come true,” I asked, “what would you like to see happen when we get to Washington at the end of the march?” Iris’s enthusiastic reply came first. She’d apparently been formulating the vision in her mind’s eye for a while. “At least a million Americans and citizens of other countries will join us in Washington, D.C. for the march to the U.S. Capitol!”

“President Reagan will address us,” Joel chimed in boldly, “saying that at one time he believed that people had to live in fear and by fear but that by our courage, determination and willingness to demonstrate, he now sees the possibility of a peaceful world and has outlined a step-by-step plan to establish a new economic policy based on education rather than consumerism, and a foreign policy based on the eradication of nuclear arms.”

To which Evan added, “All existing peace groups will send delegates en masse to Washington on November 15th and, more importantly, they will decide on that day to unite in a true global coalition for peace in the world and in space.”

“Wow,” I said, “Okay, Mayor Marion Barry will declare Washington, D.C. a nuclear-free city, and Tip O’Neill, Speaker of the House, will appear to announce an Act of Congress confirming Barry’s proclamation, and urge governors in all state capitals to follow suit… and invite Moscow to become Washington’s sister city.”

The four of us fell silent. The potential we created glowed like a campfire. The GPM had abandoned its original vision of grandeur, but our lofty hopes for a new paradigm had not diminished.

A few days walking and we were in St. George, Utah. The word around camp was that St. George was home to some of the most conservative people in America and that we should be prepared to encounter some animosity. Negative rumors had ceased to hold much sway with me. We had ignored the warnings about the dangers of crossing the Mojave, and we had ignored the naysayers who insisted that Las Vegas would shut its doors to us, and we relished the fact that we had completely ignored David Mixner’s advice back on Stoddard Wells Road that we all pack it in and go home. Like most of my fellow marchers, I was learning to take a “wait and see” attitude about negative rumors—or positive ones, for that matter.

I joined a small group of marchers to go “tabling” at a local shopping center. In the same way the Girl Scouts set up tables in front of the grocery stores to sell Thin Mints and Trifoils, we displayed pamphlets about nuclear disarmament information along with buttons, caps and t-shirts for sale. From what I could tell, local interest in our cause ranged from lukewarm to cool, but no one was impolite, much less belligerent.

An hour or two later, when we were done tabling, we heard great news. The story was that a local businessman had been returning from a business trip when he saw us trundling along the road and decided we needed a break from roughing it. He owned the nearby Green Valley Resort and invited the entire peace march for a holiday at his spa. For a few hours we lived the high life. We set up camp in a nearby parking lot and enjoyed the Green Valley Resort showers, swimming pools, Jacuzzis and sports center. Some marchers played tennis or basketball; others lounged by the pool and bought drinks at the bar. I donned my bathing suit and headed for the hot tub.

|

| Peace Marchers Arrive at Green Valley |

|

| For a Few Hours, We Lived the High Life |

The hot tub was already packed with six or seven marchers. After a few minutes, a couple of people left and I settled into the warm, bubbly water. No sooner had I sat down than the marcher sitting next to me, an older man whom I didn’t know, with a shiny, bald head and a hairless chest, started to massage my shoulders. The shoulder massage was a commonplace pass time on the peace march second in popularity only to the foot massage. People sometimes formed a circle and gave each other shoulder massages. If someone in the dinner line started massaging the shoulders in front of him, soon the whole line was engaged in one long shoulder massage. In the hot tub, however, after a minute or two, the hands of the old, bald man began to move away from my shoulders and traveled southward, threatening to trespass onto private property. Even though I had only been in the water for a few minutes, I looked at the others, all of whom could see what was going on and said, “Okay, gotta go!” as I arose from the bubbles and headed for the showers.

Later on, I told Evan and Bill and Iris how creepy that bald guy was. They laughed and said I should avoid standing in front of “Hot Tub Man” in the dinner line.